Misty Copeland’s determination now world’s inspiration

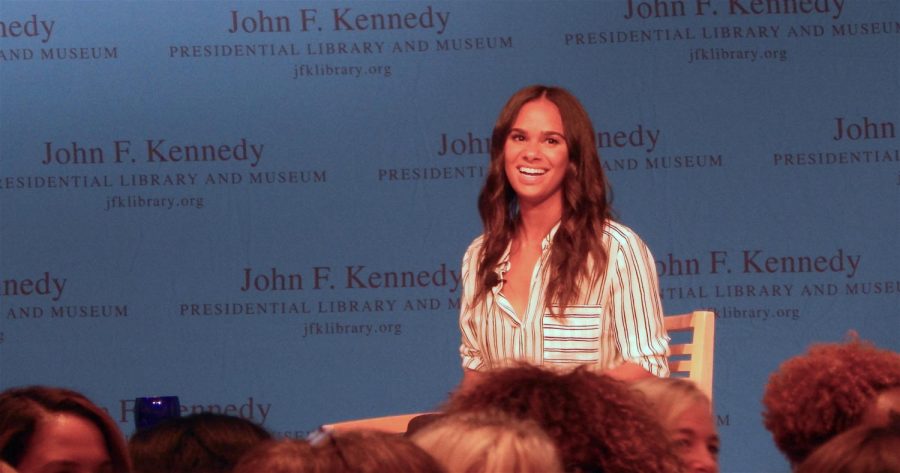

Misty Copeland, principal dancer for the American Ballet Theatre, listens to a question from the audience at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum on Aug. 28, 2017.

September 6, 2017

When Misty Copeland walks into the room, it instantly lights up. Her smile is infectious and the applause roaring from those seated all around at the JFK Library on Aug. 28, 2017, would make almost anyone want to join in the celebration of this ballerina.

Everyone loves her, and honestly, it is hard to find something not to love.

Copeland, as she sits with perfect posture across from a moderator, is well-spoken and honest. To some, maybe a little too honest. She tells of how she was born breached, or feet first, her need to move starting at the very beginning of her life.

As a child, she was “always moving, needing to feel that connection with myself.”

Young Misty was not the person to sing when a song came on; she had an “innate need to move” when she heard music. Though she was “not exposed to the arts or formal dance,” dancing was her “escape.”

Misty was one of six children, and the self-proclaimed “quiet, shy one.” She states that she wrote journals, but was never one for confrontation. During her childhood, she was “unaware of the chaos” in her life. Her mother, five siblings, and she lived in a motel for a period of time, and it was shortly after this that she discovered ballet. She worries that if she had not, she “may have fallen in with the wrong crowd” or “gotten lost.”

Copeland began ballet classes at the Boys and Girls Club in Southern California when she was 13 years old. The railing at the motel served as Misty’s barre when she practiced outside of class. She had been “waiting for something structured [and] disciplined,” in her life when she was introduced to the art.

Though she “got good grades” because she “memorized things,” and was a “Virgo,” and therefore “hardworking,” she “didn’t really connect to anything in school.”

Soon after her first lessons began, Misty was discovered at the Boys and Girls Club. A white female instructor named Cynthia Bradley found her when searching to create diversity in her program. After three months of dancing, she was already on pointe. Her body was “naturally flexible,” but the strength necessary was “not what [her] body could naturally do.” She had an “ability to watch and mimic, which can only take you so far, but it took [her] far.”

Bradley did not know her student lived in a motel. She was “good at keeping secrets,” including that she was on food stamps. The young dancer was traveling hours away to come to class and hours back each time. When Misty told Bradley she had to stop dancing because dance was “too much of a responsibility,” her teacher told her she had to at least let her give her a ride home. Misty protested, not wanting Cynthia to find out her situation. Eventually, she acquiesced.

When they arrived, Cynthia found out the truth. She saw that there were six people living in one room, and Misty had no bed. After getting halfway home, Bradley turned around and asked Misty’s mother if Misty could come live with her.

Copeland trained for four years before she became a professional. At 17, she moved to New York alone to dance with the American Ballet Theatre. There were “holes in [her] technique” because she had danced for a significantly shorter period of time than the others. When she was younger and training at a summer intensive in San Francisco, she felt like an “outsider because [she’d] only been dancing for a year and a half.”

As she went pro, Misty became more aware that the ballet world was one without a lot of people of color. Misty realized she was the only black woman in her class, and she heard people talk about her. They spoke of how long it had been since there had been a professional ballerina or principal dancer of color. As this went on, she went about learning the history of people of color in ballet, and the “lack of diversity” became “bigger than [her].”

For a time, Copeland was required to wear powder that lightened her skin, to make the dancers look “more uniform.” After a while, she realized this was crazy. She should not have to lighten herself in such a way. The other dancers wore the makeup to make them look shiny and “otherworldly.” She would ask to wear makeup of her own skin tone that would have the same effect on her that it had on the white dancers.

Misty was lucky: the ABT said yes. However, some dancers are not so lucky, she says, and would be told to do what they were told or leave.

Not only is Copeland aware of ballet’s lack of diversity, she is working to fix it. With the American Ballet Theatre, she has launched a diversity project called Project Plié, which aims to create opportunity and mend the gap between the amount of white dancers and minority dancers in the ballet community.

Misty Copeland is modest: She downplays an injury that should have ended her career.

She is determined: She explains that she kept going to different doctors until one told her there was a possibility of her dancing again.

She is engaging: She tells a young dancer who questions her that she, too, had to dance on pointe at the bar at first (“Been there girl!”).

Any time a child asks her a question, her radiant grin returns. Her vivacious laugh is as charming as her confessed hatred for fouettes, and she entertains the audience with her admittance that she and her non-dancing siblings were known for the “Copeland calves” before she began ballet training.

The standing ovation as Misty exits says it all. The woman who is known to her family as a “little mouse” because of her introverted tendencies has no reason to fear speaking; she is as graceful in conversation as she is on her toes and in the air.

Though she is still criticized “on blogs that [she is] fat” or that she has “the wrong body” just because she is black, she maintains that “the mirror is not there to criticize yourself.”

Everyone is important, and I hope that this inspirational dancer knows just how important she is to all those who want to escape to the safe place that is the stage along with her.

–Sept. 6, 2017–